Definition

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is formed by the articulation between the acromion (“shoulder tip,” A) and the distal end of the clavicle (C). The term “shoulder separation” is not a great term to describe the injury, but it is most commonly used. An AC joint injury is not a true dislocation or injury of the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint, but rather a separation of the clavicle from the acromion. The injury usually results from a fall directly onto the shoulder “point” or from a direct blow to the side of the shoulder during a contact sport, resulting in compression of the shoulder girdle. AC joint injuries make up approximately 9% of injuries to the shoulder girdle (they are quite common!).

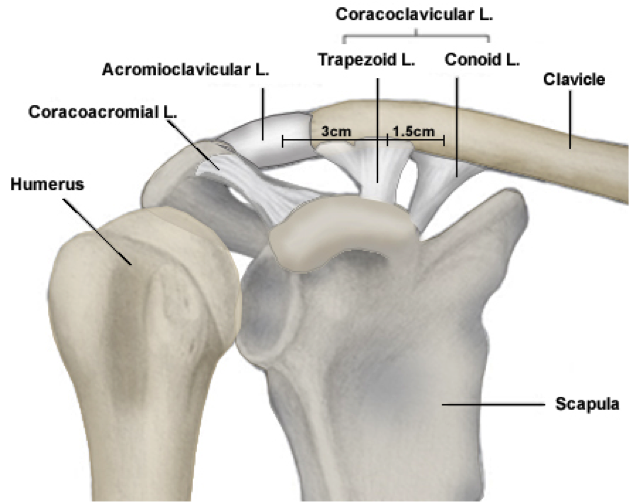

Anatomy

The AC joint is stabilized by the acromioclavicular ligament and AC joint capsule, and two ligaments that run between the clavicle and the coracoid, the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments, specifically the trapezoid and conoid ligaments (see illustration below). AC joint separations result in injury to one or more of these ligaments, depending on the severity of the injury. The result is pain and instability of the AC joint with a palpable bump at the shoulder tip where the end of the clavicle may be palpable below the skin.

Patient Presentation

An AC joint injury results from a direct blow to the side of the shoulder and is often sustained from falling directly onto the shoulder tip. The injury is commonly seen in contact athletes that are prone to lateral compression against the shoulder (ex. hockey players being body checked against the boards; football players landing or being tackled against the turf). Symptoms include pain directly over the AC joint and an obvious deformity or abnormal contour of the tip of the shoulder, depending on the severity of the injury. The patient will report difficulty and pain with shoulder motion, particularly with cross-body adduction of the affected arm.

The typical shoulder “bump” seen with high grade separations is shown here.

The XRays confirms a Type V AC joint separation, with the CC distance > 100%.

Diagnosis

Most commonly, injury to the AC joint can be diagnosed on clinical exam. The patient will report an acute injury and will have pain and bruising over the top of the shoulder in the area of the AC joint, usually with an abnormal contour or deformity of the shoulder compared to the contralateral side. In severe cases, there will be a palpable gap across the AC joint, with the end of the clavicle projecting up from the shoulder tip. The diagnosis and severity of the separation is confirmed with plane Xrays, comparing the injured and uninjured sides for grading of the injury. The coracoclavicular (CC) distance, as determined by an AP view of the shoulder, is used to quantify the grade of sprain and classify the injury (see below). An axillary lateral view or a Zanca view of the shoulder is sometimes necessary to confirm the injury depending on the direction of clavicle separation.

Differential Diagnosis

- Distal clavicular fracture

- Coracoid fracture

- AC joint osteoarthritis

- Distal clavicle osteolysis

Classification

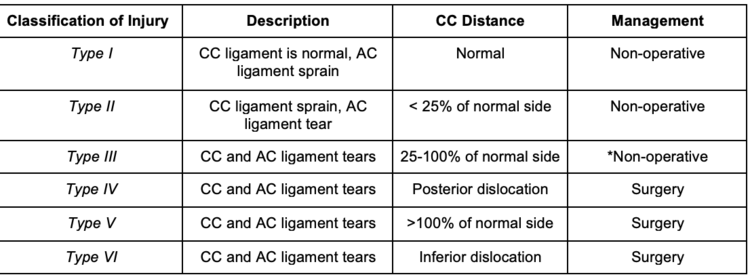

Injuries of the AC joint are classified according to the Rockwood Classification and graded as I through VI. An AP radiograph of the shoulder is used to measure the CC distance and grade the injury accordingly.

The Rockwood Classification of AC joint injuries.

Nonoperative Management

Type I and II (and usually grade III) injuries are treated nonoperatively. Nonoperative treatment includes a brief period of immobilization in an arm sling, rest, ice, and physical therapy. An arm sling is typically used for patient comfort to limit motion of the affected shoulder for the first 2 weeks following the injury and is discontinued as the patient’s pain decreases. The patient should begin physical therapy within a week of the injury, focusing primarily on regaining range of motion and strength of the affected shoulder. Rehab should focus on early range of motion, with functional motion achieved by 6 weeks. Return to sport typically occurs within 6 to 8 weeks of the injury with appropriate management. Complications of nonoperative treatment include AC joint arthritis and chronic shoulder instability. Occasionally, Type III injuries fail conservative management and may progress to Type V injuries, requiring surgery.

Historically, the management of type III AC joint injuries has been a controversial topic, with some surgeons advocating for primary surgical treatment following the injury, rather than a trial of conservative, non-operative care. Studies have shown, however, that improved outcomes of Type III injuries can be achieved with nonoperative management, avoiding the potential complications of surgery and the possible need for future surgery for hardware removal.

Studies On Management Of Type III Injuries:

- Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. (CORR 2007).

- Practical management of grade III acromioclavicular separations. (CJSM 2008).

- Decision making: operative versus nonoperative treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. (Clin Sports Med 2003).

- Open Reduction and Tunneled Suspensory Device Fixation Compared with Nonoperative Treatment for Type-III and Type-IV Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocations: The ACORN Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. (JBJS 2018).

- Operative Versus Nonoperative Management of Acute High-Grade Acromioclavicular Dislocations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. (JOT 2018).

- Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Nonoperative Versus Operative Treatment of Acute Acromio-Clavicular Joint Dislocation. (JOT 2015).

- Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment of Rockwood type-III acromioclavicular dislocation: A meta-analysis. (Medicine 2018).

- Results of Operative and Nonoperative Treatment of Rockwood Types III and V Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation: A Prospective, Randomized Trial With an 18- to 20-Year Follow-up. (Orthop J Sports Med 2014).

Operative Management

Surgical intervention is reserved for patients with Type IV, V, and VI injuries. The patient may undergo coracoclavicular (CC) interval restoration through either an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) or ligament reconstruction method. Surgery is also indicated for patient with chronic Type III injuries who have failed a conservative course of care, or progressed to a Type V injury pattern. Historically, it was thought that acute injuries were treated with ORIF and chronic injuries required CC ligament reconstruction. However, newer literature has shown no difference in outcomes in types III injuries treated surgically with ORIF after 6 weeks of nonoperative treatment versus immediate surgery.

Post-operative rehabilitation is critical to a patient’s overall outcome. As a result, surgical management is not optimal for patients who are not willing to comply with their specific post-operative rehabilitation program. Following surgery, the patient is immobilized in a sling for 6 weeks with no range of motion. Patients typically return to activity around the 6 month postoperative mark. Complications of surgery include AC joint arthritis, residual pain, hardware malfunction and coracoid fracture.

Studies:

Rehabilitation of acromioclavicular joint separations: operative and nonoperative considerations. (Clin Sports Med 2010).

Return to Sport and Clinical Outcomes After Surgical Management of Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation: A Systematic Review. (Arthroscopy 2018).

Surgery for Acromioclavicular Dislocation: Factors Affecting Functional Recovery. (Am Surg 2017).

Continuous Loop Double Endobutton Reconstruction for Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation. (AJSM 2015).