Definition

The hip joint is formed by the articulation between the head of the femur and the acetabulum, or socket, of the pelvis. This is a classic ball-and-socket joint (the head of the femur forms the ball; the acetabulum creates the socket). Normally, the femoral head is perfectly round, sitting in the perfectly round acetabular socket. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is caused by abnormal contact between the femoral neck and the acetabular rim as the hip moves through its physiologic range of motion. Bony abnormalities can occur on either the femoral side (cam impingement) or the acetabular (Pincer impingement) sides, but most commonly occur together (mixed- or combined-type FAI). The abnormal bony lesions lead to tearing of the acetabular labrum, which lines the acetabulum rim, causing pain in the hip and the development of osteoarthritis over time, if left untreated.

*The term “cam” comes from camshaft, where the cam is attached to a cylinder (think: femoral neck), creating a cylinder with a rotating irregular shape. (Link)

*The term “pincer” is more self-explanatory, in that the abnormal anatomy resembles a crab’s claw.

Anatomy

The proximal femur and acetabulum typically articulate without abutment through a physiologic range of motion (ROM). However, the required ROM differs from patient to patient, depending on their activity, and the ROM will be dependant and related to the boney native anatomy of the hip. A sedentary patient will require less range of motion, whereas an extreme range of motion might be required for activities such as dance, ballet, and ice hockey, for example. Normally, the acetabulum is anteverted 12 to 16.5 degrees and covers the femoral head to a depth that avoids both impingement (overcoverage) and instability (dysplasia or undercoverage) with a horizontal, thin sourcil (the weight bearing zone). The proximal femur normally has a spherical, concave head-neck contour and appropriate offset between the head and neck that allows for impingement-free ROM. Typically, the angle of the femoral neck-shaft angle is 120 to 135 degrees, and the femoral neck is normally anteverted 12 to 15 degrees. As mentioned above, the rim of the boney acetabular cup is lined by a fibrocartilaginous structure called the labrum (similar to the glenoid labrum of the shoulder). The acetabular labrum functions to create a fluid pressurization seal with the femoral head. It also occurs in continuity with the articular cartilage liner of the joint. As a result, tears of the acetabular labrum eventually begin to extend into the cartilage lining the joint, resulting in “chondral delamination” of the joint and, eventually, osteoarthritis.

Pathogenesis

Femoroacetabular impingement is categorized into three different subtypes:

A. Pincer-type Impingement: Contact between the abnormal acetabular rim and femoral head-neck junction.

A pincer lesion is usually the result of a deep acetabulum (coxa profunda), focal anterior overcoverage, acetabular retroversion, or, less commonly, posterior overcoverage. This leads to labral bruising and degenerative tearing which may ultimately result in ossification of the labrum and a contrecoup posterior acetabular chondral injury. Pincer-type impingement is predominantly found in middle aged women.

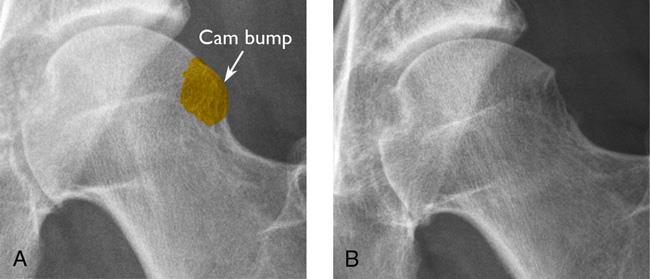

B. Cam-type Impingement: Contact between the acetabular rim and an abnormal femoral head-neck junction. The abnormal femoral head–neck junction is typically secondary to an aspherical anterolateral head–neck junction but also can be secondary to a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), femoral retroversion, coxa vara, a malreduced femoral neck fracture, and, less commonly, posterior femoral head–neck abnormalities. A CAM-type impingement causes a shearing stress to the anterosuperior acetabulum, with predictable chondral delamination and labral detachment and tearing. CAM-type impingement is predominantly found in young, male athletes (90%).

C. Mixed- or Combined-Type Impingement: The most common form of FAI involves a combination of BOTH cam and pincer lesions, creating an abnormal articulation between the acetabular rim and the femoral head-neck junction.

D. Extra-Articular Sources of Impingement: Recently, Anterior Inferior Iliac Spine (ASIS) Impingement has been recognized as a form of Femoroacetabular Impingement. The AIIS is the origin of the head of the rectus femoris muscle, and impingement can occur secondary to a prior avulsion fracture or pelvic osteotomy, or can develop in the event of acetabular retroversion. Although rare, Ischiofemoral Impingement is a noted type of proximal-femoral based impingement that occurs between the lesser trochanter and ischial tuberosity. As a result, the quadratus femoris muscle can be compressed because it occupies this space between the LT and ischial tuberosity. Normal distance between the lesser trochanter and ischial tuberosity is 20 mm. However, with ischiofemoral impingement, the space between these sites can decrease, causing this form of impingement. Women are at greater risk for ischiofemoral impingement due to their wider pelvis and resultant lateralization of the ischial tuberosities.

Natural History

There is no known evidence that confirms that a patient with untreated FAI will undoubtedly develop osteoarthritis, due largely to a paucity of longitudinal long-term data. However, clinical correlation with over 600 surgical dislocations of the hip in patients with FAI has depicted a strong association of this disorder with progressive acetabular chondral degeneration, acetabular labral tears, and progressive osteoarthritis of the joint. Patient with symptomatic FAI will, however, develop a progressive chondral and labral injury which could then lead to progressive osteoarthritis of the joint, if left untreated and allowed to progress. One population study suggests that there is a 15% to 19% prevalence of a deep acetabular socket (pincer lesion) and a 5% to 19% prevalence of pistol grip deformity (cam lesion) of the hip. This population had a relative risk ratio of developing hip osteoarthritis of 2.2 to 2.4, illustrating the association between FAI boney abnormalities and arthritis.

It is well known that there is a high prevalence of FAI imaging findings in asymptomatic patients (Arthroscopy 2015, Euro J Radiol 2016, AJSM 2015). This should emphasize the importance of both the patient history and physical examination in overall assessment of the patient.

Patient History

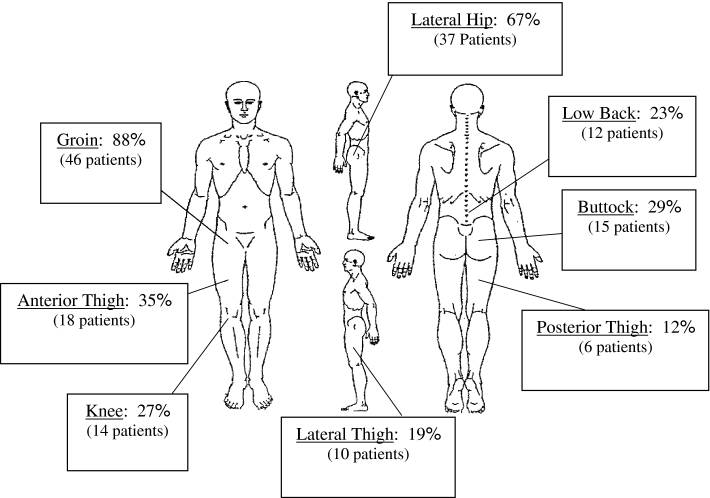

Typically, patients are young to middle aged and present with a variety of symptoms ranging from predominantly anterior groin pain to lower back or buttock pain. Anterior groin pain is the most common presenting symptom. The symptoms are typically aggravated by activities such as running, skating, yoga, sitting for extended periods of time, standing up from a seated position, putting socks and shoes on, sitting with legs crossed, and getting in and out of vehicles. Patients often complain that their symptoms are beginning to affect their sleep at night and not being able to get into a comfortable position in bed, often resulting to sleeping with a pillow between their legs (a pillow between your legs will help prevent the adducted, internally rotated position that typically worsens FAI symptoms and anterior groin pain). Symptoms may also be present or mild in the contralateral hip. Patients have often been (mis)diagnosed with other conditions such as chronic lower back pathology, hip flexor strains, and sports hernias/athletic pubalgia and may have had past surgeries for pain relief, often misdiagnosing or completely missing their pathologic hip condition.

This study by Clohisy et al (CORR 2009) illustrates the variety of presenting symptoms in patients with symptomatic FAI and some of the common dilemmas of misdiagnosed hip pain in patients suffering from FAI: “The average patient age was 35 years and 57% were male. Symptom onset was commonly insidious (65%) and activity-related. Pain occurred predominantly in the groin (83%). The mean time from symptom onset to definitive diagnosis was 3.1 years. Patients were evaluated by an average 4.2 healthcare providers prior to diagnosis and inaccurate diagnoses were common. Thirteen percent had unsuccessful surgery at another anatomic site. On exam, 88% of the hips were painful with the anterior impingement test. Hip flexion and internal rotation in flexion were limited to an average 97 degrees and 9 degrees, respectively. The patients were relatively active, yet demonstrated restrictions of function and overall health.

Physical Exam

The physical examination is critical in the diagnosis of FAI, which aims to classify the subtype of impingement through a series of tests that exacerbate the patient’s symptoms by putting the hip into vulnerable positions and motions that may reproduce the impingement, causing discomfort.

-

ROM tests: Global ROM restriction generally suggests advanced osteoarthritis.

-

Anterior Impingement Tests: FADIR (Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation)

-

Posterior Impingement Tests

-

FABER Distance Test: Flexion, Abduction, and External Rotation of the hip. An increased distance from the lateral knee to the examination table may indicate femoroacetabular impingement. (Reference: Trindale et al. KSSTA 2018)

-

For subspine impingement, the physician may examine for pain with straight flexion, restricted flexion, and, more likely than not, tenderness to palpation of the AIIS that recreates the flexion-based discomfort.

-

For ischiofemoral impingement, the physician may examine for pain with extension, adduction, and external rotation (ER).

-

Evaluation of femoral version/torsion and acetabular version

Imaging

Radiographs (X-rays) should be taken of the anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, a frog-leg lateral, 45-degree and 90-degree modified Dunn views, and false-profile view.

An MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) or MR-Arthrogram may be ordered to evaluate the following:

-

Labral and chondral pathology

-

Acetabular version

-

Femoral head-neck junction deformity

-

Femoral neck version: Impingement may be caused by retroversion or torsion (anteversion and torsion can result in instability)

-

Synovial herniation pits/impingement cysts at the femoral head

-

Occasionally, an anesthetic agent (lidocaine combined with corticosteroid) can be included with the gadolinium to verify the hip joint as the source of pain.

A Three-Dimensional CT Scan can be helpful in order to:

-

Further assess the boney morphology of the hip joint

-

Increase accuracy and understanding of the joint

-

Assess the hip joint for complex revision cases

-

Confirm subtle cases of FAI

-

Evaluate femoral version/torsion and acetabular version

Differential Diagnosis

-

Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia/core muscle injury

-

Osteoarthritis of the hip

-

Femoral neck stress fracture

-

Lumbar spine pathology

-

Gynecologic or urologic pathology

-

Intra-abdominal pathology

-

Hip flexor pathology or iliopsoas snapping

-

Iliotibial band (ITB) pathology or snapping

-

Other extra-articular myotendinous pathology

-

Abductor/gluteus medius/minimus pathology

-

Pelvic stress fracture

-

Apophysitis or apophyseal injury in the developing skeleton

-

Intra-articular pathology not related to FAI

-

Extra-articular hip impingement

-

Neurogenic disorders

Nonoperative Management

Nonoperative management approach to FAI included stretching, activity modification, and physical therapy focusing on core and abduction strengthening and ROM. Other options include medications such as anti-inflammatories and analgesics. Intra-articular hip injections are aimed to decrease inflammation within the joint rather than cure the underlying pathology, and may include corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), or mesenchymal stem cells (BMAC).

Operative Management

The primary indication for surgery in FAI is failure of a course of conservative management and exacerbation and progression of symptoms despite conservative management. Dr. Dold treats FAI through hip arthroscopy, utilizing 2 to 3 keyhole incisions around the hip. An arthroscope is utilize to visualize the joint pathology, while small instruments are used to remove the boney lesions and repair the acetabular labrum.

To set up a hip consultation with Dr. Dold, click here.

YouTube of Dr. Dold’s arthroscopic labral repair and osteochondroplasty technique can be viewed here.

Dr. Dold’s article on post-operative considerations following hip arthroscopy can be found here.

Visit Dr. Dold’s YouTube channel for more surgical technique videos: