Definition

Pectoralis major tendon rupture is a rare injury most commonly seen in male athletes, especially in weight lifters performing heavy bench press. This is because in the bench press position, the arm is abducted and externally rotated which places the muscle under maximum tension. Pectoralis rupture can also be seen in wrestlers, water sports, football players, and rugby players. Anabolic steroid use can predispose patients to this injury. The site of rupture predominantly occurs at the musculotendinous junction or insertion of the tendon on the humeral shaft.

Anatomy

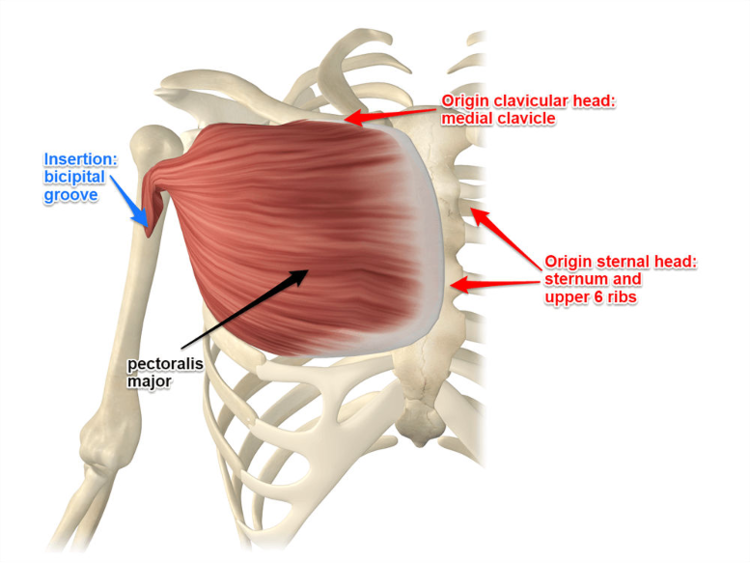

The function of the pectoralis major muscle is to adduct, internally rotate, and flex the shoulder. It originates from two heads, the clavicular head and the sternocostal head. The clavicular head arises from the medial clavicle and proximal sternum while the sternocostal head arises from the distal sternum, ribs 1-6, and the external oblique aponeurosis. These muscle fibers converge and insert onto the humeral shaft, lateral to the bicipital groove.

Anatomy of the pectoralis major muscle

Patient Presentation

The patient will present describing an acute injury where a “pop” is felt near the shoulder or armpit followed by immediate onset pain and weakness. There is typically significant associated soft tissue swelling and bruising along the chest wall and/or upper arm. Often times, there is an obvious deformity seen from retraction of the pectoralis muscle belly medially. This is known as “dropped nipple” sign. Strength testing will reveal weakness with resisted adduction and

internal rotation.

Diagnosis

Pectoralis major tendon rupture can be diagnosed based off of history and physical exam alone but an MRI is typically ordered to confirm diagnosis, determine whether there has been a partial or full thickness tear, and determine location of retracted tendon stump. X-rays are almost always normal, however, if a bony avulsion has occurred this will be evident on plain films.

Classification

Modified Tietjen (Anatomic) Classification

Type 1

-

Muscle contusion or sprain

Type 2

-

Partial tear

Type 3

-

Complete tear (further classified by location)

-

3A – Muscle origin

-

3B – Muscle belly

-

3C – Musculotendinous junction

-

3D – Intratendinous rupture

-

3E – Tendon avulsion off humerus (no bone)

-

3F – Bony tendon avulsion off humerus

-

Management

In young active patients, surgery is generally recommended to repair the tendon back down to its attachment site on the humerus. The operation provides adequate recovery of strength and most patients are able to return to their sport at pre-injury levels 6 to 12 months post-operatively. When considering whether to treat non-operatively vs operatively, it is important to understand that both options lead to regaining full range of motion and decreased pain. However, surgery is essential to regain pre-injury strength. Active patients who are treated non-operatively are typically unable to return to previous athletic ability. Complications of surgery are rare but include persistent pain, re-rupture, residual weakness, infection, bleeding, and damage to neurovascular structures.

Nonoperative management can be utilized for low-demand, sedentary, or elderly patients. Partial thickness tears and tears within the muscle belly may also heal well without an operation.