Definition:

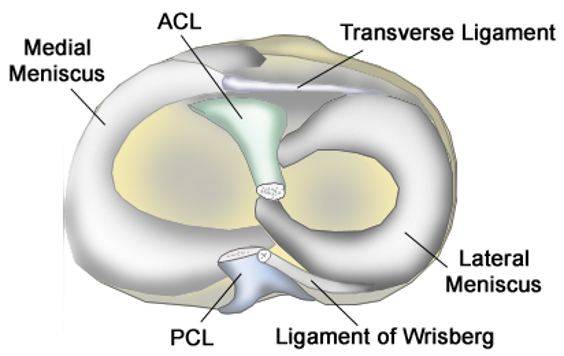

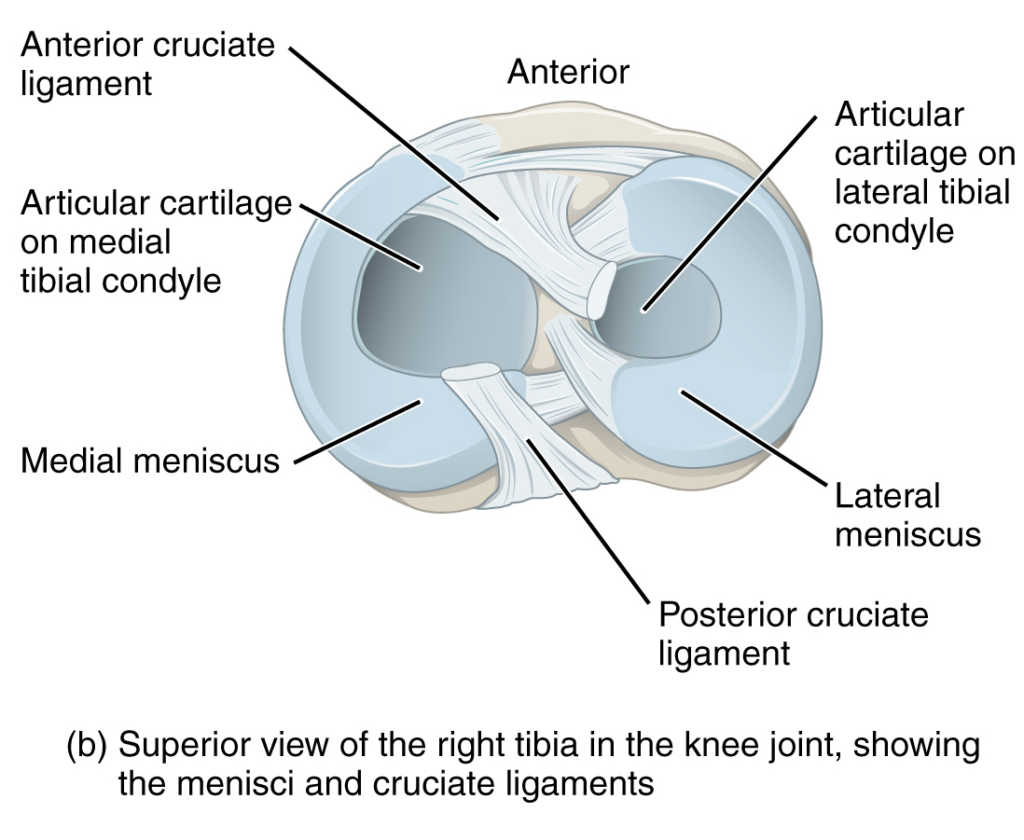

The knee contains two c-shaped menisci: medial and lateral. Menisci are crucial to knee function and joint health. These structures help to stabilize the knee while optimizing force transmission. A disruption in one or both of the meniscus can cause pain, swelling, and mechanical symptoms (clicking, catching, and popping) in the knee, especially with activity. Options for the surgical treatment of meniscal tears include debridement (partial meniscectomy) and meniscal repair.

Anatomy:

The menisci help to distribute loads and stresses on the knee joint. They are made of fibroelastic cartilage. 90% of the collagen they are composed of is Type 1 collagen. The lateral meniscus is useful with posterior movement while the medial meniscus is involved in preventing anterior translation with extension. In an ACL deficient knee, the menisci become imperative stabilizers of the knee joint. To optimize force transmission, the menisci increase contact surface area and absorb shock using their radial and longitudinal fibers. Each meniscus is divided into three distinct zones: white zone, red-white zone, and red zone. The white zone is the furthest inside the knee and has no associated blood flow. The red-white zone is in the middle of the meniscus and has some degree of blood flow. The red zone is the far outer portion of the meniscus and typically has a good vascular supply. This area is supplied by the middle genicular artery and has good healing potential after a meniscal repair. Blood supply is an important consideration in injury healing. Meniscus tears in the central zone have limited natural healing capability.

Etiology:

Everyone is susceptible to a meniscal tear! Meniscal tears are common in athletes as well as in older individuals. Meniscus tears are often associated with a single acute event such as a twist or quick turn that creates a shear force to the meniscus. Additionally, there can be degenerative tearing associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. A medial meniscus tear is more common than a lateral meniscus tear and are the most common indication for knee surgery. ACL tears can be a risk factor to meniscal tears.

Clinical Presentation:

Patient will often experience knee pain localized to the affected meniscus(medially or laterally). Pain is exacerbated by activities that involve weight bearing such as squatting, lunging, running, etc. Patients may have difficulty sleeping at night due to the pain or discomfort. Pain is often associated with mechanical symptoms such as popping, clicking, catching, or buckling of the affected knee. A knee effusion can be present with more severe mechanisms of injury.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of a meniscal tear may be suspected by your provided after a through history and physical examination.

Physical exam:

Patients often present with tenderness along the joint line (medial or lateral). A positive McMurray’s test, is also a good indicator of meniscal pathology. Other physical exam findings include: positive Apley and Thessaly testing. Global ROM restriction generally suggests advanced osteoarthritis of the knee.

Imaging:

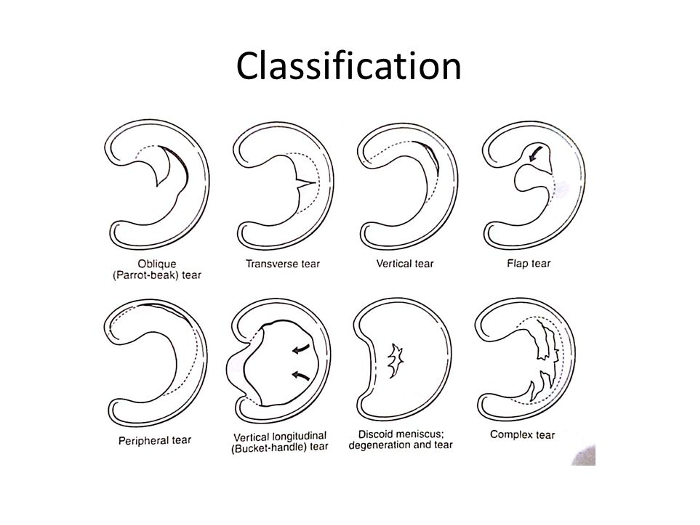

Traditional radiographs are often obtained to rule out a fracture or degenerative process within the knee joint (ex. arthritis). If radiographs are clear of fracture or arthritis, an MRI will likely be ordered to assess the soft tissue structures of the knee. MRI imaging is the image study of choice for diagnosis of a meniscus tear. Though, with knee osteoarthritis, an MRI is often unnecessary for diagnosis as meniscal tears are a common and somewhat expected finding in advanced arthritis of the knee. MRI may reveal a parameniscal cyst associated with the meniscal tear. Classification of meniscus tears are based on their direction, location, size, and pattern of the tear.

Pathogenesis:

- Vertical/Longitudinal – Common and frequently seen concurrently with an ACL injury (typically involving the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus).

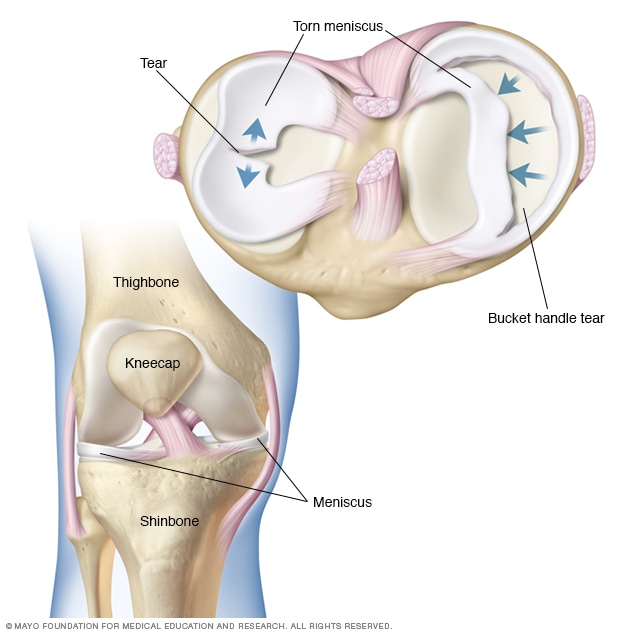

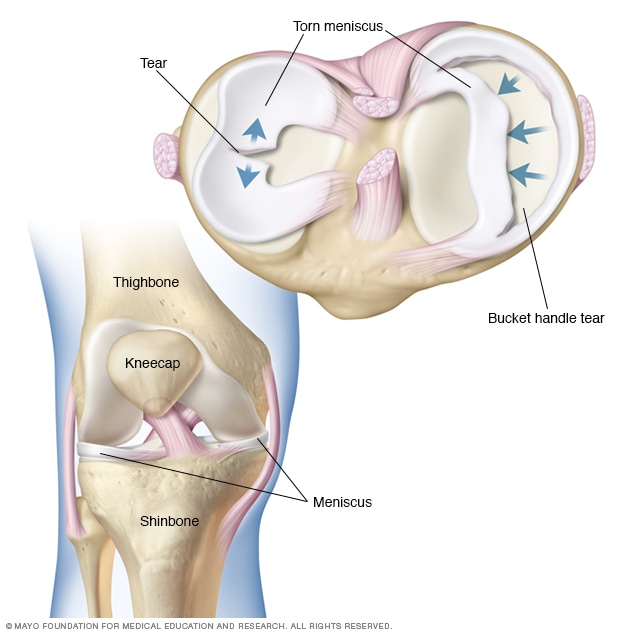

- Bucket handle – A vertical tear that displaces a large portion of the meniscus into the intercondylar notch of the knee, which makes ROM difficult especially with knee extension. On MRI, double PCL or double anterior horn sign may be visualized, indicating a bucket-handle tear. Bucket handle meniscal tears most commonly involve the medial meniscus.

- Radial – When a radial tear involves the posterior root attachment of either the medial or lateral meniscus, meniscal extrusion often results. In this case, a meniscal root repair is required to restore normal meniscal anatomy and mechanics.

- Horizontal – Most commonly seen in the older population

Differential Diagnosis:

- Osteoarthritis of the knee

- Patellofemoral syndrome (PFJ syndrome)

- IT band syndrome

- Tibial stress fracture

- Lumbar spine pathology

- Apophysitis

- Bone contusion

- Knee sprain

- MCL sprain

- Plica syndrome

- Osteochondral lesions

- Pes anserine bursitis

Treatment options:

Meniscal tears are treated conservatively or with surgical intervention. The decision for a surgical operation is based on several factors including a patient’s age, the type of tear, symptoms, activity demands, and coexisting pathology of the joint (ex. arthritis).

Nonoperative management options:

- NSAIDS (ex. Meloxicam, Celebrex, Naproxen)

- Activity modification – Rest, activity modification, limit exercises/activities that increase pain and symptoms.

- Physical therapy – Focus on strengthening the surrounding muscles, modalities,

- Injections – Corticosteroids, Platelet-rich Plasma (PRP), Stem Cell therapy.

- Knee bracing

Operative management:

Meniscal tears are the most common indication for knee surgery. Surgical intervention for an isolated meniscus tear is often completed as a knee arthroscopy to address the meniscal pathology using a camera for visualization of the knee joint. A knee scope may involve a partial meniscectomy, trimming out a small portion of the torn meniscus, or a meniscal repair (stitching the meniscus back together). Ideal candidates for meniscal repairs are those with tears in the well vascularized red zone of the meniscus, vertical and longitudinal tears, root tears, tears combined with ACL reconstruction, and tears in younger individuals. Meniscal repair can be achieved utilizing meniscal repair suture devices. Meniscal repair techniques include: inside out, all-inside, outside in, and open repair. Tears located in the white zone, with little to no blood supply, are often treated with a partial meniscectomy, attempting to preserve as much meniscal tissue as possible. If the meniscus tear is present in the setting of significant osteoarthritis, the knee may be replaced and a total knee arthroplasty is performed. Recovery time depends on the procedure performed. Meniscus repair requires adequate time for healing of the repaired tissue and typically takes approximately 6 months to heal. Patient’s undergoing meniscal repairs are often six weeks non-weight bearing utilizing crutches in the initial post-operative period. Partial meniscectomy patients typically do not require as long to heal and crutches are not necessary post-operatively.

To schedule a knee consultation with Dr. Dold click HERE.

YouTube of Dr. Dold’s arthroscopic partial meniscectomy can be viewed HERE.

YouTube of Dr. Dold’s arthroscopic meniscal root repair technique can be viewed HERE.

Related articles:

- Bhatia S, LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, LaPrade RF. Meniscal root tears: significance, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2014.

- Biomechanical consequences of a complete radial tear adjacent to the medial meniscus posterior root attachment site: in situ pull-out repair restores derangement of joint mechanics.

- Beaufils P, Pujol N. Meniscal repair: Technique. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018.

- McDermott I. Meniscal tears, repairs and replacement: their relevance to osteoarthritis of the knee. Br J Sports Med. 2011.

- Krych AJ, LaPrade MD, Cook CS, Leland D, Keyt LK, Stuart MJ, Smith PA. Lateral Meniscal Oblique Radial Tears Are Common With ACL Injury: A Classification System Based on Arthroscopic Tear Patterns in 600 Consecutive Patients. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020