The hallmark features of patellar tendinopathy are: (1) pain localized to the inferior pole of the patella and (2) load-related pain that increases with the demand on the knee extensors, notably in activities that store and release energy in the patellar tendon (ex. jumping sports like basketball). While imaging may assist in making an accurate diagnosis, the diagnosis of patellar tendinopathy remains clinical, as asymptomatic tendon pathology may exist in people who have pain from other anterior knee sources. A thorough examination is required to diagnose patellar tendinopathy and contributing factors. Management of patellar tendinopathy should focus on progressively developing load tolerance of the tendon, the musculoskeletal unit, and the kinetic chain, as well as addressing key biomechanical and other risk factors. Rehabilitation can be slow and sometimes frustrating. Platelet-rich plasma is often used as an adjunct to a solid rehabilitation program to help expedite recovery.

Definition

Patellar tendonitis, often referred to as “Jumper’s Knee,” is a common injury seen in the orthopedic and sports medicine clinic. The hallmark features of patellar tendinitis are: (1) pain localized to the inferior pole of the patella and (2) load-related pain that increases with increasing use of the knee extensors, notably in activities that store and release energy in the patellar tendon (ex. jumping or running). While imaging may assist in making the diagnosis, patellar tendinopathy remains a clinical diagnosis, as asymptomatic tendon pathology may exist in people who have pain from other anterior knee sources (ex. Runner’s knee or PFJ syndrome). A thorough examination is required to diagnose patellar tendonitis/tendinopathy and contributing factors. The management of patellar tendinopathy should focus on progressively developing load tolerance of the tendon, the musculoskeletal unit, and the kinetic chain, as well as addressing key biomechanical and other risk factors. Rehabilitation can be slow and sometimes frustrating. Anti-inflammatory medications and injections can also help in treatment.

“Jumper’s Knee”

Blazina et al (Orthop Clin North Am, 1973) first used the term jumper’s knee (patellar tendinopathy, patellar tendinosis, patellar tendinitis) in 1973 to describe an insertional tendinopathy seen in skeletally mature athletes, although Sinding-Larson, Johansson, and Smillie once described this condition (aka. Sinding Larson Johansson Syndrome, SLJS). Jumper’s knee usually affects the attachment of the patellar tendon at the inferior patellar pole. The definition was subsequently widened to include tendinopathy of the attachment of the quadriceps tendon to the superior patellar pole or tendinopathy of the attachment of the patellar tendon to the anterior tuberosity of the tibia. The term jumper’s knee implies functional stress overload due to jumping and can affect any area of the patella tendon, including its origin at the inferior pole of the patella or its insertion at the tibial tuberosity.

Anatomy

The patellar tendon is a connective tissue that connects the distal pole of the patella (knee cap) to the front of the tibia (shin bone). It is an important part of the extensor mechanism of the knee and aids in extension, or straightening, of the knee. It is a continuation of the quadricep tendon, which connects the four quadriceps muscles of the thigh to the patella. The patellar tendon then runs from the inferior pole of the patella and attaches distally onto the front of the tibia at the tibial tuberosity. This attachment at the tibial tuberosity allows for extension of the knee and is important in the extensor mechanism that aids in activity such as jumping, landing, and sprinting.

Pathogenesis

Tendonitis is a chronic inflammatory process of the connective tissue that makes up a tendon. Patellar tendonitis results from constant mechanical stress exerted on the extensor mechanism that aids in jumping and extending the knee. This constant mechanical stress leads to micro-trauma of the tendon that causes cellular damage and leads to small tears within the tendon. This cellular damage is what activates the inflammation process and causes pain with activity. Broken down, tendon-itis = tendon + inflammation. If left untreated for an extended period, chronic inflammation can set in and cause chronic tendinosis. Patellar tendinosis is the chronic form of acute tendonitis and can potentially lead to more serious injuries due to the tissue architecture being weakened. This can lead to patellar tendon tearing or even patellar tendon rupture.

Natural History

Minor sports injuries like patellar tendonitis often go unreported, this makes it hard to determine the frequency of patellar tendon injury. However, there has been a high prevalence of tendinosis related to the increase in jumping sports such as volleyball, basketball, as well as long and high jumping. Patellar tendinitis can be seen in adolescent athletes as well as adults into their third decade of life and is more likely to be seen in males over females.

Patient History

The diagnosis of patellar tendonitis can usually be made in the clinical setting with a good history and physical exam. The patient will report an increase in activity that is associated with jumping as well as a slow increase in pain along the anterior aspect of the knee with no apparent injury or trauma. The pain will most likely be localized at the anterior aspect of the knee along the inferior pole of the patella, extending into the proximal aspect of the patellar tendon. Patients may also complain of pain that is not associated with jumping, but exacerbated but other activities such as going up or down stairs, lunging, or getting up from a seated position from a prolonged period of sitting. This pain is usually short lived and is associated with “loading” the tendon. Once the load is removed the pain diminishes.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical exam will help diagnose patellar tendonitis. The clinician will take the patient through a series of tests that will assess the entire knee. Patients may exhibit localized pain and swelling at the anterior aspect of the knee along the patellar tendon as well as tenderness to palpation along the inferior pole of the patella and along the length of the tendon. Another physical exam finding could be the “passive extension – flexion sign”. In this test the examiner will passively extend the affected leg and palpates the patellar tendon to find the point of maximal tenderness. They will then flex the knee to 90 degrees and palpate the same location. A decrease in tenderness is a positive finding and is indicative of patellar tendinopathy. Another sign would be the “standing active quadricep sign,” when the patellar tendon is palpated with the leg fully extended and then palpated again at approximately 30 degrees of flexion. The test is positive if the pain is markedly decreased with palpation of the tendon while the knee is in a flexed position.

Imaging

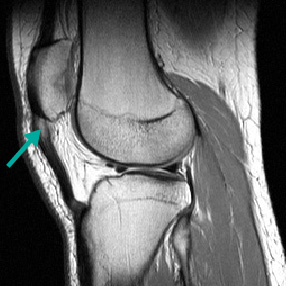

Plain radiographic films of the knee are typically normal in patellar tendinopathy. These films can help rule out any additional pathologies such as avulsion fractures, osteoarthritis, and calcification of the patellar tendon. Often, if calcification of the patella tendon is seen on plain radiographs, chronic patellar tendinopathy is usually the culprit. Another radiographic finding that can be seen on plain radiographs is an osteophyte along the inferior pole of the patella, called an enthesophyte. Enthesophytes can be caused by long standing traction from the chronically tight and inflamed patellar tendon. Calcification of the patellar tendon can also be seen in severe cases (see picture bottom left). MRI is usually not required to make the diagnosis of patellar tendonitis, but can help identify the source of inflammation, confirm the diagnosis (bottom right image), and rule out other pathologies. MRI is reserved for surgical planning for procedures such as patellar tendon reconstruction in cases where the patient has suffered a complete rupture of the patellar tendon from chronic tendinopathy.

Non-operative Management:

Treatment is primarily aimed at conservative care with anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS), injections (PRP or orthobiologics), and physical therapy. It is important to establish the diagnosis early and get ahead of the condition as it can become a progressive worse disease if left untreated (patella tendonitis becoming patella tendinopathy). Activity modification to include rest from excessive jumping rather than strict immobilization is crucial. Along with adequate rest, a stretching protocol to increase flexibility of the quadriceps and hamstring musculature is a mainstay. With any tendinopathy, eccentric loading is believed to play a major role in the physical therapy process. This eccentric loading helps increase blood flow to the tendon while placing stress throughout range of motion. The physical therapist may also utilize taping or specific bracing to help reduce tension across the tendon. In addition to physical therapy, injections that utilize biologics can help facilitate tendon healing. These injections can be in the form of PRP or BMAC. Both are biologic injections that aid in healing and reduction of inflammation from an autologous source.

Dr. Dold has had tremendous success in treating athletes suffering from patella tendonitis with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and an early functional rehabilitation protocol focusing on early eccentric loading of the tendon in conjunction with PRP. We utilize a PRP formula with a higher concentration of leukocytes in order to mobilize the vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) within the white cell, producing a neoangiogenesis effect within the tendon. The allows for the formation of new blood vessels that function to heal and restore normal tendinous tissue.

Operative Management:

In our experience, surgical management is rarely required for the management of patella tendonitis. This is usually reserved for patients who have partial interstitial tears within the tendon and continue to have pain at rest, despite an extended period of conservative care and physical therapy. This procedure is a patellar tendon debridement to remove the chronically damaged tissue within the tendon to help restore normal tendon architecture. Surgical debridement is often performed with concurrent use of orthobiologics, including PRP and BMAC.

Relevant Studies and Research:

- Clinical Outcomes, Structure, and Function Improve With Both Heavy and Moderate Loads in the Treatment of Patellar Tendinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

- Rethinking Patellar Tendinopathy and Partial Patellar Tendon Tears: A Novel Classification System.

- Platelet-rich plasma in tendon-related disorders: results and indications.

- Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy.

- The evolution of eccentric training as treatment for patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee): a critical review of exercise programmes.

- Isometric exercise and pain in patellar tendinopathy: A randomized crossover trial.

- Management of Patellar Tendinopathy Through Monitoring, Load Control, and Therapeutic Exercise: A Systematic Review.

- Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness.

- Management of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy: what we know, what we can do.

- Effectiveness of progressive tendon-loading exercise therapy in patients with patellar tendinopathy: a randomised clinical trial.

- Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations.

- Biomechanics of the knee extensor mechanism and its relationship to patella tendinopathy: A review.

- Patellar tendonitis and patellar dislocations.

- The Impact of Hyaluronic Acid on Tendon Physiology and Its Clinical Application in Tendinopathies.

- Can ultrasound imaging predict the development of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis.

- The effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in common lower limb conditions: a systematic review including quantification of patient-rated pain reduction.

- Patellar tendinopathy.

- Patellar tendonitis and anterior knee pain.

- Inertial flywheel vs heavy slow resistance training among athletes with patellar tendinopathy: A randomised trial.

- Common overuse tendon problems: A review and recommendations for treatment.

- Clinical Management of Patellar Tendinopathy.

- Patellar tendonitis: clinical and literature review.

- Decreasing patellar tendon stiffness during exercise therapy for patellar tendinopathy is associated with better outcome.

To schedule a consultation with Dr. Dold, please fill out a form online, and someone from our office will be in touch with you within 24 hours to confirm your appointment.